Back in 1959, the first set of National Competition Rules for Towing Cars (Appendix J} was drafted and approved by CAMS, to apply from January 1, 1960. A young bloke tom the bush called Des West, who was as skilled at spannering Holdens as he was at driving them, took a standard Holden 48-215 and turned it into a competitive race car that complied with the new rules. West and his father Lindsay ran the local Holden dealership at VI/Ingham, near Taree on the NSW mid-north coast.

A qualified mechanic. young Des had been up to his elbows in Holden for more than a decade and knew them like the back of his grease-stained hands. It didn't cost him a lot of loot to build this car and the finished product positively bristled with homemade, hand-fettled performance tweaks gleaned from years of mucking around with cars from an early age. It was quintessentially Austra ian, this early touriig car racing. No factory teams, mega-dollar budgets or flashy workshops. It was all about doing a lot with not a lot; choosing the best car you could afford and drawing on your set of skills to get the best out of it. Finding out what made it tick, learning through trial-and-error how to make it go faster. And, no doubt, through more trial-and-error, how to drive it faster, too! Today, this immortal 48-215 is, as far as we know, the only original and un-restored survivor from that first ATCC race at Gnoo Blas, NSW in 1960. Its original owner/builder/driver, Des West, after spending many hours inspecting it in fine detail, has personally verified its authenticity. The fact that it still exists in suci unmolested, original condition, wit most of West's authentic circa-1960 'hot-rodding' tricks still kited, is something of a blessing for those of us with a tine appreciation of Vie past. This is the way we went touring car racing when the Australian Touring Car Championship was born. Join us on a sobering journey to discover just how much the sport of touring car racing - and the cars we drove in it - have changed in 50 years.

48-215: Australia's Own Car Is Born

The first production version of Holden's 48-215 rolled off the GM-FI production line at Melbourne's Fisherman's Bend plant on November 29, 1948. heralding the birth of a teal' car manufacturing industry in Australia, making Australian cars for Australian people.

The 48-215 was a four-door sedan featuring 'unibody' construction (body/ chassis built as one unit) and built on a 103•inch (2616mm) wheelbase.

At 4.4 metres in overall length, just over 1.7 metres in width and standing just under 1.6 metres tall, its compact dimensions added up to a kerb weight of just over a ton (1011 kgs). More than two years after the 48.215 sedan was launched, a 215 utility model was also made available for the man on the land.

Powered ay a 132.5cid (2171cc), overhead valve, six cylinder engine, with 6.5:1 compression and rated at 60bhp (45kWi at 3800rpm, the only transmission available was a three-speed manual with column shift.

Brakes were four-wheel drums and the suspension was a simple and rugged

coil spring/ upper & lower control arm arrangement with lever-type

shocks at the front, with a leaf-sprung live rear axle under the tail

comprising a banjo-type hypoid differential.

With good fuel economy and a decent-sized fuel tank of just under 10 gallons (43 litres) in capacity. Australia's first car could cover 400kms between fills, with performance considerably better than many of the stodgy British offerings available at the time. And, for the price. it was a bargain.

Not surprisingly, the Holden was an instant hit with the Aussie public and buyers eagerly joined long waiting lists at GM-H dealers around the country. Production lines at both Fisherman's Bend (Victoria) and Woodville (South Australia) were soon running at full capacity to try and meet this demand.

Holden's

48-215 production continued until October 1953, when it was replaced by its face-lifted successor - the FJ. In that time, GM-H produced more than 120,000 48-215s in a combination of sedan and utility styles.

World of Outlaw! 1950s Touring Car Racing

If you weren't around in the 1950s, you could be excused for thinking that Australia's long-standing love affair with touring car racing has existed since 'Australia's Own Car' became a reality.

However, back then touring car racing was in fact very much the second tier of the sport; a poor cousin to the 'purist' open-wheeler and sports car set that headlined major race meetings.

Competing in cars with doors and roofs was looked down upon by the racing elite; it was something that people with oily rags in their back pockets and grease under their fingernails drove because they couldn't afford a 'real' racing car.

|

| Leo Geoghegan's famous black 48-215 featured aerodynamic tweaks to

increase speeds like grille-mounted wind deflectors and a smoother

under-body - even the headlights got dome-shaped covers to reduce drag |

Perhaps because of that, touring car racing's popularity - amongst competitors at least -enjoyed healthy growth in the '50s, helped along by the undeniable fact that it wasn't too hard or expensive to squeeze some decent speed out of Holden's readily available 48-Series Holdens (48-215 anc: FJ) and later the FE model released in 1956.

They were also in plentiful supply (both the cars and their spare parts), cheap to buy and maintain and they responded well to modifications.

In fact, it wasn't long before a thriving aftermarket industry was established, supplying a myriad of locally-developed performance parts (including complete cylinder heads, like Repco's popular 'Hi Power' unit developed by Phil Irving) and tuning tips to get the best out of them. There were also disc brake conversions, body streamlining, big pistons and valves, wild camshaft grinds and specially-made racing wheels.

|

| Repco's twin-carb 'Hi-Power' cylinder head was popular with early Holden racers |

Extreme measures to reduce weight were also employed, including stripped-out interiors, removal of bumper bars even production of lightweight aluminium panels. At a time when the annual Redex Round Australia Trials were still commanding most of the headlines for sedan car competition, the level of competition amongst the 1950's circuit-racing crowd was becoming very serious indeed. And a growing problem for the sport's administrators. Up untel 1960, there was no national set of rules for touring car racing; different circuit promoters had different regulations, which only encouraged increasingly uncontrolled levels of modification. Towards the end of the decade, things were clearly getting out of hand. By then, one 48-series Holden racer featured an engine bay stuffed full of a Waggott twin-cam cylinder head conversion; there was also an Austin Lancer with a full MGA twin-cam donk shoehorned into it; Peugeots, Morrises and Austins were even running full-blown superchargers.

The 48-Series Holden 'guns' of the era were John French and Leo Geoghegan, driving cars so heavily modified that their links to the showroom products they outwardly represented were becoming increasingly thin. For example, French's ferocious two-tone green FJ featured a very trick Repco cylinder head designed for triple Weber carbs, a Jaguar four-speed gearbox with floor shift and was rumoured to be runring high octane alcohol fuel -one of the few things that was illegal. At one stage, French even took a large slice out of the FJ's bonnet - from the top of the grille right back to the windscreen - and welded in a section of flat steel sheet to create a large sloping `wedge' to reduce aero drag! And Geoghegan's now legendary black 48-215 featured a unique aluminium Repco cylinder head on a wickedly hot 'grey' motor claimed to be punching out 167bhp (125kW) - or almost three times that of the standard engine.

|

| Don't let the tame two-lone green paint and bicycle tyres fool you - John French's highly modified FJ was stove-hot! |

There was also a four-speed gearbox - from an MG - and even some thoughtful aerodynamic aids, including wind deflectors mounted either side of the grille to improve air penetration and a smoother under-body to tidy and speed up airflow under the car. Considering that Lotus czar Colin Chapman didn't start playing around with the science of ground effects under his Fl cars until the mid 1970s, this was cutting-edge stuff! Clearly, though, 'tin top' racing had become a world of outlaws. With no national set of rules to keep these blokes in line, the cars were now reaching alarming levels of modification and performance. Drivers were becoming increasingly concerned about where this was all heading. Not before time, change was on the way.

Law and Order: Appendix J

Up until the early '50s, motor sport in Australia was run by the Australian Automobile Association (ANN), appointed by the Royal Automobile Club of Great Britain. This quaint but increasingly dysfunctional arrangement lasted until 1953, when motor sport's international controlling body, the Federation Internationale de L'Automobile (FIA), officially recognized the newly created Confederation of Audtralian Motor Sport (CAMS) as the local governing body. Fortunately, by the end of the decade, CAMS acknowledged a pressing need for a uniform and sensible set of national rules for touring car racing, if the category was to build on its burgeoning popularity with both competitors and spectators.

So, as a new decade dawned, CAMS made two major announcements that would prove pivotal. Firstly, a new set of National Competition Rules for Touring Cars would apply from the start of the 1960 season. And secondly, in recognition that touring car racing was becoming a major force in the sport, 1960 would also host the first Australian Touring Car Championship (ATCC), that would be held annually and contested over a single race of at least 50 miles (80 kms). Put simply, the highly-modified 'sports sedans' of the 1950s, with their non-standard cylinder heads and gearboxes, huge brakes, stripped interiors, lightweight panels etc could compete in a new hybrid Grand Touring class called 'Appendix K' where they would share the road with closed sports cars. And a new class called 'Appendix J' would cater for a new breed of standardized touring cars, permitted very limited modification that would adhere much more closely to their showroom origins. Bodywork and interior trim had to remain standard, which was a good start.

|

| Above: A Holden-only race at Katoomba's fabulous Catalina Park circuit shows how popular and competitive the early model 48 Series Holdens remains, well into the 60's. |

The new rules allowed freedoms in some areas of tuning and race preparation and restrictions in others. On reflection, in some ways it was like an early version of the 1973-1984 Group C rules. Engine capacity could be increased within the class limitation that applied to a particular type of car. That was 2001-2600cc in the case of the ubiquitous `grey'- engined Holdens, which naturally prompted the boring of cylinders right out to the maximum displacement allowed. Cylinder heads had to remain stock, but valves, manifolds, camshaft and compression were free. Engine metal could not be cut, except for mild porting and polishing. Gear ratios had to remain as standard. Suspensions also had to remain stock, but could be lowered and improved for racing with 'bolt on' items like uprated springs and shocks, anti-sway bars, radius rods, tramp rods, Panhard rods and the like. Wheel rims could be strengthened and widened to a maximum 1.0-inch (25mm) from standard. Brakes had to remain standard in both size and operation, but linings were free and additional cooling was allowed.

For its time, Appendix J was a simple, sensible and cost-effective set of rules - standard road cars with a few little 'hot-ups' here and there. It was designed to encourage more drivers to compete and also appeal more to spectators, by showcasing the same cars they could go out and buy from their local dealer. Importantly, only Appendix J cars could compete for the newly announced ATCC title, so there was plenty of incentive for drivers to have a crack at this new more regulated form of touring car racing. Which they did, in ever increasing numbers, with many choosing to continue running the well-developed 48-215 and FJ Holdens, but also the odd later model FE series cars, too. Not surprisingly, the aftermarket industry for Holden 'go-faster' bits that had sprung up in the 1950s continued to flourish into the new decade, with a staggering amount of expertise available for the Humpy Holden racer that wanted it.

|

| Lindsay and Des West after their outstanding Top 20 result in the 1953 Redex Round Australia Trial. |

Nuts and Bolts: Des West's 48

For most Aussie muscle car fans, Des West needs no introduction. During the late '60s and early '70s, he was one of the top 'guns for hire' during Mount Panorama's muscle car war It was West who set a cracking pace in a privately-entered Monaro GTS 327 to lead many laps of the '68 Bathurst 500, against a swarm of Holden and Ford works cars, only to lose his second place result due to a post-race scrutineering dispute (for which he was eventually cleared of any wrongdoing). The following year, he was a star recruit for the newly formed Holden Dealer Team under Harry Firth, sharing one of three factory-backed Monaro GTS 350s with a fast rookie called Peter Brock to finish third outright.

|

| Dusty and rusty today, but 50 years ago a tweaked 48-215 was the gun machine for Holden racers to have in the new Appendix J era. |

He was also a works driver for Chrysler in 1970, winning his class at Bathurst in the factory's 4BBL Valiant Pacer. In later years, he also drove the legendary Falcon GT-HO Phase III and Charger R/T E49 at the Mountain. West's prominence in Bathurst history is well deserved. However, his path to national recognition had started many years before, when he partnered his father Lindsay in the inaugural Redex Round Australia Trial in 1953. Driving a self-prepared FJ Holden, the Wests completed all stages and finished an outstanding 19th outright on debut, with young Des doing most of the driving. The experience wet his appetite for competition. He continued to compete in the Round Australia Trials and numerous club events.

By the late 1950s, though, he wanted to have a more serious crack at circuit racing, so he built himself his first dedicated competition car. And this is that car. The same one that would later compete in the first Australian Touring Car Championship race in 1960. So, let's have a close look at it:

Car:

Its a 1953 model 48-215. West wanted a 48-215 as the basis of his race car, mainly because it was 50 lbs (23 kgs) lighter than the FJ model. However, he specifically wanted one of the 'late production' versions produced during GM-H's transition from 48-215 to FJ production in 1953, which were fitted with the first of the FJ's improved components like the latest telescopic shocks (as opposed to the 48-215 lever-type), wider rear leaf springs, stronger front cross-member etc. Des specifically tracked down this car for the purpose.

West's Garage had sold it to an elderly local couple a few years before, who literally only drove it to church on Sundays. Des tracked them down through the Garage's sales records and did a deal to secure the car. You may have noticed by looking at the engine bay and inside the door jams that this old Humpy was originally a rather bland light blue/grey in colour.

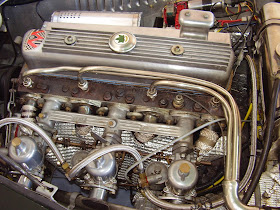

|

| West's hand-built Holden engines were noted for their great power and

sky-high rev tolerance. 7000rpm from a triple-carbed grey in 1960 was

remarkable. |

|

| Forged lumpy-top pistons gave 13.5:1 compression. |

When he started racing it, Des painted the roof section black to try to make the car stand out more on the track, which was how the car looked when it ran at Gnoo Blas in February 1960. However, no doubt inspired by those wonderful cars. from Italy with the prancing horse badge that did a lot of winning, he reckoned red racing ears just had to be faster, so later in the year he painted his car red, too.

Engine

“When it came to winding out an engine, Des left 'Big Rev Key' for dead," claims former RCN editor and 48-series Holden racer Max Stahl. "On at least two occasions, Des out-dragged me when I pulled top at six-two (6200rpm), while he went on to well over 7000! I couldn't afford the crankshafts."

After building so many hot Holden engines in the '50s that he kist count, by the time of the first ATCC in 1960, Des West had become a self-taught master in putting together some very strong and powerful Holden grey motors for racing.

When this car's current owner Allan Garfoot carefully removed and stripped down its engine for a thorough inspection, he discovered a multitude of modifications that made this engine amongst the strongest of its era.

Starting from the top, the standard cast iron grey motor cylinder head (as required by the Appendix J rules) was fully ported and polished and fitted with bigger valves, dual valve springs, lightweight aluminium retainers and pushrods.

It was mated to the standard grey cylinder block using a special Repco composite head gasket, made from a copper/asbestos/copper sandwich with copper firing rings to withstand the sky-high compression ratio.

Three GP Amal 1 3/8-inch, single-barrel, side-draught motorcycle carbs delivered a solid strea of fuel/air mixture to the inlet ports through homemade inlet manifolds, which were basically long straight lengths of metal tube (for increased torque) that delivered a nice clean shot straight into the cylinder head.

The exhaust manifold was also a custom-made item; 1 3A-inch diameter pipe created a simple three-into-two-into-one arrangement, with a large single muffler and exhaust pipe exiting under the kerb-side passenger door.

The engine's bottom-end featured stronger billet steel caps on the centre main bearings, for greater crankshaft strength and stability at high revs.

The cylinders were over-bored to boost displacement to just under the 2600cc class limit and filled with Repco forged 'lumpy top' pistons pumping 13.5:1 compression ratio on 110-115 octane Avgas.

The standard con-rods were balanced by 'tinning' each rod and then slowly filling them with solder between the webs. This allowed the weight of each rod to be adjusted to make a finely balanced set.

The standard sump was fitted with a handmade windage tray to stop the crankshaft from frothing the oil and some baffles to reduce oil surge during hard cornering.

Oil temperatures in racing were always a worry, so the capacity of the standard sump was increased to a whopping 8.0 litres by slicing off the base of the oil pan and extending it downwards, so that it ended up hanging in the breeze much closer to the road.

West took advantage of this by welding a line of small steel tubes into the base of the sump. These were open at either end, to allow air to pass through and cool the oil (above).

And there were other oil management tweaks. For example, the engine did not have an oil filter fitted as standard (!) but Holden at least made provision for an accessory oil filter if required.

The unit West tapped into the side of the block featured a tap handle on top, attached to an internal vane which when turned a couple of times scraped any collected sediment through a fine grate into a cup below, that could be easily removed for cleaning (left).

West installed an additional line to direct an extra dose of oil from the same gallery to the camshaft's distributor drive, which at high revs tended to run a bit lean of lube and was prone to failure (below left).

On the back of the crankshaft, the standard flywheel was heavily machined and drilled to reduce internal masses for improved throttle response. Before the days of drilled bolt heads and lock-wiring, simple locking plates for the flywheel bolts were made from strips of sheet steel, with tabs bent over the heads to prevent them working loose.

At the front of the crank, a Jaguar harmonic balancer - which was larger and heavier than the standard item — helped to tame a serious crankshaft vibration that occurred at a certain point high up in the rev range.

West removed the engine's cooling fan to reduce air drag and therefore power losses.

The radiator was also later modified. The standard 48-215 outer frame and header tank were retained, but the core was a special high-density unit commonly used on farm tractors, which often have to pull heavy loads at low speeds with minimal air flow.

The tractor core's series of rectangular cooling tubes were positioned at a slight angle to the airflow, allowing a larger number of tubes per square inch and therefore greater coolant capacity and total (cooled) surface area.

The 48-215's standard windscreen wipers were operated by vacuum pressure from the engine's intake manifold. They worked great under hard acceleration, but were pretty ordinary at other times!

To combat this problem for racing, West mounted a large vacuum tank on the driver's side firewall (where the original 6V battery once lived) with enough capacity to maintain reasonable wiper speeds at all times (bottom left).

This tank was fed by a hose from the inlet manifold, that split at a T-piece to supply vacuum pressure for both the wiper tank and the brake booster diaphragm.

To maintain good fuel pressure, West couldn't rely on Holden's standard camshaft-driven mechanical fuel pump. He instead installed twin SU electric fuel pumps in the boot (one sucking, one pumping) right next to the fuel tank.

This fuel set-up, plus the sky-high 13.5:1 compression ratio, demanded plenty of electrical grunt and cranking power. So West upgraded the standard 6-volt system to a 12-volt arrangement, with the twice-as-large 12v battery relocated to the boot for better weight distribution (less weight on the front axle).

Another simple change was made to the grille, with the centre 'tombstone' section modified so that it could be quickly removed for camshaft changes without having to hoist the engine out of the car each time. To do this, all the original grille rivets were drilled out and removed, leaving the centre section held in place by just four self-tapping screws.

Small metal hoops were also attached either side of the grille and bonnet, through which short leather belt straps with buckles were threaded and tightened.

That was because the rules demanded that, in addition to the standard bonnet catch, a secondary form of securing device had to be fitted to ensure the bonnet could not fly open at speed. Leather straps like these proved a low-cost and popular solution.

There was also a restraining cable strung tightly between the bell-housing and the gearbox cross-member, to stop the engine and drivetrain shifting forward under hard deceleration and potentially nosing into the radiator core.

Clutch/Gearbox/Tailshaft

Between the lightened flywheel and standard three-on-the-tree manual transmission was a heavy-duty clutch assembly with stronger pressure plate springs and a meatier driven plate to cope with the extra power and general abuse.

Any casting 'dags' on the inside of the cast-iron gearbox casing were ground off and polished smooth, to improve oil flow in and around the gears and shafts. Larger and thicker bearing races and circlips were also fitted to provide extra strength and durability, along with a larger breather.

The tailshaft was fully balanced. West also knocked up a simple tail-shaft loop made, from steel strap, which was bolted to the underside of the floor behind the shaft's front universal joint. This was designed to catch the shaft in the event, of a front uni joint breaking at speed, to stop it dropping down v. and harpooning into the road with potentially disastrous results. These loops are standard fitment in all RWD competition sedans.

Diff Basically stock inside, as demanded by the Appendix J rules, which did not permit welding of planetary gears etc to create a pair of 'locked' rear axles for better traction. However, West did at least fit substantially thicker shims to the axle shafts to try to tighten things up and legally reduce the differential effect.

Brakes Front

Back in 1960, when four-wheel drum brakes were the rule rather than the exception in touring car racing (unless you could afford a Jaguar or other exotic), providing effective heat management was always top of the job's list. Even so, West says these cars would run out of brakes after just a few hard laps!

The front drums remained at the standard diameter as demanded by the rules, but special 'fan' castings with a series of lateral fins provided much greater heat dissipation than the standard items. In standard form, each drum assembly featured brake shoes of unequal length. West replaced the shorter shoes with the longer shoes in each drum, to increase the total friction area available. Shoe linings were made from an asbestos/sintered brass friction material designed to withstand high temperatures and Chevrolet hydraulic cylinders (with larger bores than the Holden items) increased fluid force on the brake shoes for greater stopping power.

Additional cooling came from large air scoops hand-fabricated from thin metal sheet that attached to the front of the backing plates, which were heavily drilled at the front to allow cooling air to enter and at the back to allow hot air to escape.